Brexit 410AD

The event and date - “Brexit 410AD” - was when Britain ceased to be an official part of the Roman Empire and was left to its own devices. What triggered this divorce?

Many reasons are offered why the Roman rule of Britain gradually weakened. Military problems there were for sure, but there were also climatic reasons. The Roman Warm Period, famously the period when grapes were grown as far north as York, gradually gave way to a colder and wetter climate, just as it also grew colder all over Northern Europe. Crops yields would have dropped, pressuring the populations with hunger or starvation, and motivating populations to move south.

Back to the military problems : Britain had for (at least) 30 years provoked nothing but trouble for Rome, with rebellious natives and disaffected troops. The Roman garrison on Hadrian’s Wall may have been caught up in this, as it is recorded that it rebelled in 367AD. The historian Ammianus :

provides an account of the tumultuous situation in Britain between 364 and 369, and he describes a corrupt and treasonous administration, native(?) British troops (the Areani or Arcani) in collaboration with the barbarians, and a Roman military whose troops had deserted and joined in the general banditry.

Ref : Attacotti and Areani

In AD 383 Maximus Clemens Magnus, a Spaniard related to a Welsh family, was proclaimed emperor by his troops over the Gaul Preafectura, while serving with the army in Britain. Later legend made him King of the Britons; he handed the 'throne' over to Caradocus when he went to Gaul to pursue his imperial ambitions. In Brittany (Gaul) Maximus had appointed one of his loyal friends Conan as 'administrator'. Conan’s successors would bear the title of king. This appointment suggests that many of the high-ranking officers in Maximus' army were of Welsh origin, and that the Welsh had supported his ambition financially.

Ref : ProtoEnglish : The events before the 5th century

The Welsh Emperor of the Roman Army (for a while).

Theodosius I and Valentinian II campaigned against Magnus Maximus in July-August 388 AD. Maximus was defeated in the Battle of the Save, near Emona, and retreated to Aquileia. Andragathius, magister equitum (general) of Maximus and killer of Gratian, was defeated near Siscia, his brother Marcellinus again at Poetovio. Maximus surrendered in Aquileia and although he pleaded for mercy, he was executed.

It didn’t stop there. Just 18 years later, another General in Britain was claiming the title of Emperor.

Constantine III, "the usurper" was proclaimed emperor in Britain by the legions in AD 406. His (honorific) name referred to Constantine the Great and expressed his ambitions. In AD 411 his adventure eventually failed and he was beheaded by Constantius, emperor Honorius' general. It is thought that Constantine had left so few troops in Britain that the isle became easy prey for Saxon and other raiders (Saxons = Vikings). Shortly after Constantine III went to the continent, the 'Roman' (tax) administration was destitute ... At that moment, all taxes were sent to the continent in support of Constantine’s ambitions. Britain was deprived of the means to defend itself against the raids.

This is how the whole "Anglo-Saxon" mythology got started, with the locals having to hire private mercenary troops to defend themselves from Danish and Viking raiding parties.

British' envoys went to Emperor Honorius in AD 410 in an attempt to normalize the relations with the Empire. They also needed soldiers to stop the incursions. The eastern, proto-English side of the isle was lukewarm about the Empire. On top of that, many eastern lords hired more and more private guards, often led by Anglo-Saxons, and that was against the (Roman) law. ... Those local guards were the only ones who effectively defended the country. The unthreatened western, proto-Welsh side was far more pro-Roman, but exactly that (overzealous) side had betrayed Honorius. On top of all that, the central tax administration had been dissolved.

But the envoys didn’t get the help they’d hoped for. They were told to carry on paying their tax revenue to Rome but not to expect the benefits the taxes payed for.

What Honorius did was unprecedented: he told the British officially to defend themselves. The emperor no longer took responsibility for Britain. Defending the empire and assuring its security was the main task of the emperor. This was not quite a declaration of independence, as Britain had in theory to pay taxes. The purpose of those taxes was to pay the legions which had to defend the borders. So Britain now had to finance its own defense and had to contribute to the defense of the rest of the Empire.

Ref : ProtoEnglish : Honorius decides not to decide

Who were the Romans in Britain?

From our school history classes, most of us have a hazy idea that the Romans were, err, Romans that arrived c.50AD, and then somehow stayed Roman for c.300 years, but then just got up and left Britain, c.400AD. This is an illusion, as most "Roman" troops in Britain were not Romans. At least, certainly not Romans when they started their military service. Roman citizenship was only granted to retiring soldiers after twenty-five years of service. And many stayed in Britain when their service was complete.

How so?

It was normal practice for Roman army veterans to receive an honourable discharge after 25 years service, and receive a diplomata (documents issued to retiring soldiers). What happened next? Did they all leave Britain as well? Or did they decided to stay in Britain? Recent DNA profiling suggests that at least some Roman Auxiliary units decided they liked Britain well enough to stay, settle down with local women, and spread their DNA in specific parts of Britain. The pioneer of this kind of DNA detective work, for British origins, has been Stephen Oppenheimer with his ground-breaking work "The Origins of the British" (2006).

One year later, Steven Bird published his work on the DNA of Roman Army units in Britain:

Haplogroup E3b1a2 as a Possible Indicator of Settlement in Roman Britain by Soldiers of Balkan Origin: The invasion of Britain by the Roman military in CE 43, and the subsequent occupation of Britain for nearly four centuries, brought thousands of soldiers from the Balkan peninsula to Britain as part of auxiliary units and as regular legionnaires. The presence of Haplogroup E3b1a-M78 among the male populations of present-day Wales, England and Scotland, and its nearly complete absence among the modern male population of Ireland, provide a potential genetic indicator of settlement during the 1st through 4th Centuries CE by Roman soldiers from the Balkan peninsula and their male Romano-British descendants.

Ref : Journal of Genetic Genealogy. 3(2):26-46, 2007

Haplogroup E3b1a2 as a Possible Indicator of Settlement in Roman Britain by Soldiers of Balkan Origin

Where did they comes from?

E3b1a2 is found to be at its highest frequency worldwide in the geographic region corresponding closely to the ancient Roman province of Moesia Superior, a region that today encompasses Kosovo, southern Serbia, northern Macedonia and extreme northwestern Bulgaria.

Where did they end up?

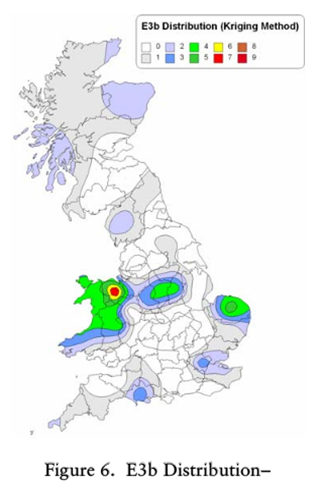

The frequency of E3b in Britain was observed to be most prevalent in two regions; a geographic cluster of haplotypes extending from Wales eastward to the vicinity of Nottingham, encompassing the region surrounding Chester, and a second (NNE to SSW) cluster extending from Fakenham, Norfolk to Midhurst, Sussex.

(c) Steven Bird, Journal of Genetic Genealogy. 3(2):26-46, 2007

Haplogroup E3b1a2 as a Possible Indicator of Settlement in Roman Britain by Soldiers of Balkan Origin

This figure, from the article by Steven Bird, most clearly shows the hot-spots of these Balkan genes in Britain.

Thracian soldiers in Roman Britain

In Rome’s Saxon Shore Fields (2006, p. 38) it is stated that under Severus Alexander (r. 222-235) it was thought advisable to withdraw troops from the northern frontier and place them in new forts built at Branoduno (Brancaster), Caister-on-Sea, and Regulbium (Reculver).

Thracian and Dacian cohorts stationed at Birdoswald on Hadrian’s Wall were well-attested epigraphically, however, from 205 to at least 276. This period overlaps with the reign of Severus and the decision to relocate Roman troops from the Wall to the Shore Forts

Bronze military diplomata (documents issued to retiring soldiers)

The diplomata were issued as formal retirement papers, proving that the soldiers had received an honourable discharge from the Roman Army. It also “granted Roman citizenship to retiring soldiers after twenty-five years of service”. An example was found near Malpas in Cheshire (now in the British Museum, item no.1813.12‐11.1‐2 in the Department of Prehistory and Early Europe). The translation by Collingwood in 1990 specifically mentions many different units serving in Britain, from different sources.

Found in 1812 in the parish of Malpas in Cheshire, on a farm belonging to Lord Kenyon' (Lysons); 'in a field on the Barhill (or Barrel) Farm, in Bickley about two miles E.S.E. of Malpas'

The Emperor Caesar Nerva Traianus Augustus, conqueror of Germany, conqueror of Dacia, son of The Emperor Caesar Nerva Traianus Augustus, conqueror of Germany, conqueror of Dacia, son of the deified Nerva, pontifex maximus, in his seventh year of tribunician power, four times acclaimed Imperator, five times consul, father of his country, has granted to the cavalrymen and infantrymen who are serving in four alae and eleven cohorts called: (1) {ala} I Thracum and (2) I Pannoniorum Tampiana and (3) Gallorum Sebosiana and (4) Hispanorum Vettonum, Roman citizens; and (I) {cohor} I Hispanorum and (2) I Vangionum, a thousand strong, and (3) I Alpinorum and (4) I Morinorum and (5) I Cugernorum and (6) I Baetasiorum and (7) I Tungrorum, a thousand strong, and (8) II Thracum and (9) III Bracaraugustanorum and (10) III Lingonum and (11) IIII Delmatarum, and are stationed in Britain under Lucius Neratius Marcellus, who have served twenty-five or more years, whose names are written below, citizenship for themselves, their children and descendants, and the right of legal marriage with the wives they had when citizenship was granted to them, or, if any were unmarried, with those they later marry, but only a single one each. {Dated} 19 January, in the consulships of Manius Laberius Maximus and Quintus Glitius Atilius Agricola, both for the second time [CE 103]. To Reburrus, son of Severus, from Spain, decurion of ala I Pannoniorum Tampiana, commanded by Gaius Valerius Celsus.

There's a lot there; here's my best guess at what that means in today's currency:

| Roman name |

Current place or country |

|---|---|

| Thracum/Thracia | Southern Balkans = Western Turkey |

| Pannoniorum Tampiana | Pannonia perhaps? |

| Gallorum Sebosiana | German? |

| Hispanorum Vettonum | Vettones tribe of Lusitania in Hispania (Salamanca in Spain) |

| Vangionum | Vangiones were a Belgic tribe from the upper Rhine |

| Alpinorum | Western Alpine |

| Morinorum | Morini tribe, from Belgica province around Gesoriacum (Boulogne, France) |

| Cugernorumn | Cugerni tribe of Germania Inferior |

| Baetasiorum | Baetasii tribe "inhabiting the lands between the Rhine and the Meuse to the immediate west of Novaesium in Germania Inferior" |

| Tungrorum | Gallia Belgica, today eastern Belgium and the southern Netherlands |

| Bracaraugustanorum | cavalry from Gallaecia, now northern Portugal |

| Lingonum | Gaul "in the area of the headwaters of the Seine and Marne rivers" |

| Delmatarum | Dalmatia (Croatia) |

There's a hell of a lot of long-distance traveling to work there. This is just one diplomata, and it mentions thousands of Roman army veterans settling in Britain. How many more diplomata were there, with how many more thousands of veterans? Frere et al., stated that

less than 20% of diploma recipients moved out of the province in which they had served upon retirement.

(RIB,v.II,2401.5,p.12).

In short, most stayed. This includes the famous Thracian cavalry units, who stayed and became Native Brits. All well before 410AD when Britain ceased to be an official part of the Roman Empire and was left to its own devices. These Thracian cavalry units have a large part to play in the genesis of Arthurian legends as well, right up to the modern day. e.g. the 2004 film "King Arthur".

The film is unusual in reinterpreting Arthur as a Roman officer rather than a medieval knight. Despite these departures from the source material, the Welsh Mabinogion, the producers of the film attempted to market it as a more historically accurate version of the Arthurian legends.

These people settled and provided continuity and stability to the communities they formed or joined, in many parts of Britain, such as Essex.

Dark (2002, pp. 97-100) has theorized that sub-Roman Essex may have survived intact until the sixth century and that the civilian authority may have transitioned smoothly from sub-Roman to Saxon authority without any evidence of struggle or the displacement of the local Romano-British population. Drury and Rodwell (1980, p.71) have provided similar evidence for the survival of sub-Roman Essex well into the Anglo-Saxon period.

Ref : Dark K (2002) Britain and the End of the Roman Empire.

The implication is that there was no Dark Age as such. See Mind The Gap! Or, the Great Myth of the Dark Ages. Just much-less written communication being sent back to Rome to provide a continuous written history. But Hadrian’s Wall deserves special mention, as it one piece of Roman Britain that is very well documented.

Hadrian was the greatest builder in history … Following the peace that he declared, the soldiers of Rome were left without a livelihood. The large building projects offered employment to the soldiers and the placement of the temples at the corners of the Empire delineated the borders of the Hellenistic culture and kept the soldiers along the border areas, far from Rome.

Some of the veteran Romans (from the army and auxiliary) had already retired, or had been made redundant or pensioned-off by Hadrian when he started fixing the boundaries and stopped trying to expand the Empire. This raises the firm possibility that Hadrian's Wall in Britain was not built for overtly military reasons, but to keep idle Roman troops busy with civil engineering projects. Especially as military engineering skills readily adapted to civil engineering skills.

The troops who manned the wall, it must be remembered, were drawn from all parts of the Roman Empire; and the bulk of these forces lived here for the next 300 years or so, intermarrying freely with the British inhabitants, and regarding Northumberland and Cumberland as their home, where they continued to live after their discharge. Thus it can be stated as a matter beyond doubt that the modern inhabitants of these counties are in large part directly descended from the Roman troops; and the curious mixture of blood which must have resulted will be realized when it is remembered that here were garrisoned generations of Asturians from Spain, Batavians from the lower Rhine, cornovii from Shropshire, Dalmatians from the Adriatic, Dacians from Rumania, Frisians from Holland, Gauls, Lingones from Langres in France, Tungrians from Tongres in Belgium, and so forth.

Ref: Wanderings in Roman Britain

What happened to Roman Christianity when the Romans left?

And so, we come to the Roman Estates in Britain. These Mithraic Roman estates had been well-established for up to 300 years, as agricultural communities.

These quietly morphed into Early Mithraic-Christian Communities. Or monasteries as we like to call them now. The same skills that had built Mithraic temples for Roman troops, administer a conquered territory, and managed the agricultural production and distribution, are identical to the skills needed to built early Christian chapels, churches and monasteries, and administer their huge estates. The brand name may have changed, but the contents of the package remained much the same.

It's worth noting that the Coptic/Egyptian/Celtic monastic system is notably different from the Romanised version. The former makes more of a feature of hermits and monasteries in isolated places. The Roman version tends to like more of a social life at the heart of a prosperous business, like the vast Yorkshire Cistercian sheep farming estates, owned and run by the monasteries. From where the valuable wool was exported to merchants as far as Italy. Or perhaps we should say especially Italy, given the Roman connection.

This could explain a few later curiosities. Like how the later-arriving Augustinians/ Benedictines/ Cistercians/ Premonstratensians et al (but especially the Tironensians) monastic orders managed to expand at such a phenomenal rate. Business growth by assimulation and takeovers is quicker and easier than starting from nothing.

What came first? Churches or Monasteries?

This is not clear-cut, as different Christian folk had different styles. Monasteries appear to have appeared in Ireland and Scotland before starting in England, whereas the earliest known English Church appear before English monasteries. Irish ecclesiastical history maintains a notable distinction from the British version.

The first reliable historical event in Irish history, recorded in the Chronicle of Prosper of Aquitaine, is the ordination by Pope Celestine I of Palladius as the first bishop to Irish Christians in 431 – which demonstrates that there were already Christians living in Ireland.

Ref : History of Ireland

The date is interesting, only 21 years after the Romans officially left Britain. Hardly any time at all. Not long enough for a Dark Age, but enough time for a void to develop that needed filling. Pope Celestine is an interesting character too.

St. Celestine actively condemned the Pelagians and was zealous for Roman orthodoxy. He sent Palladius to Ireland to serve as a bishop in 431. Bishop Patricius (Saint Patrick) continued this missionary work. Pope Celestine strongly opposed the Novatians in Rome; as Socrates Scholasticus writes, "this Celestinus took away the churches from the Novatians at Rome also, and obliged Rusticula their bishop to hold his meetings secretly in private houses.

Ref : Pope Celestine

The Pelagians might have disappeared from British History were it not for them appearing in several papal records as people who needed special attention. But why?

Pelagius (circa 360 – 418) was a British-born ascetic moralist, who became well known throughout ancient Rome. He opposed the idea of predestination and asserted a strong version of the doctrine of free will.

Ref : Pelagius

The overlap of early Christianity with civil unrest in Britain is often overlooked.

Events during the last part of the 5th century are very confusing because civil wars are typically confusing. A religious war (Pelagian heresy against Catholicism) aggravated the problems. Pelagius preached that ‘Rome’ was not necessary to go to heaven. Notice the similarity with the later Anglican Church. The Pope (not bearing this title at the time) in Catholic Rome tried desperately to regain power by sending ‘missionaries’ to convert people (read: bring them back under the rule of Rome).

Ref : Proto English

Catholic Roman control being via the Roman Army's Mithraic Christianity, not the Egyptian Coptic/Irish/Hibernian Christianity. Pelagius was clearly a threat to the business model of the Catholic Church. Just imagine - people might start waking up to the idea that they could choose to be good, and happy, all by themselves, and live fulfilling lives in their own lifetime. Why then would they need priests to tell them they are miserable sinners who could only be fulfilled after they had died? And only if they did what the priests told them to do?

The very idea that we can make a conscious choice over whether to be good or bad is still a radical concept for many people. In the psychology of Personal Development, it is allied with self-awareness and personal responsibility. That is, the ability to respond, as a healthy liberation, rather than a repressive burden imposed upon us.

We could pose the Pelagius position as simply one of individual people having a personal choice. With no judgement as to whether that is good or bad. Therefore, no jobs for the priests to make judgements on behalf of God as to whether people were making good or bad free-will choices.

As such, in current terms, perhaps that is the Libertarian -v- Authoritarian position. Of course, "Libertarian" is very much a US & French ideal, which we Brits have largely been rather uncomfortable with, ever since the French Revolution (1789 to 1799) and the arrival of the Hanoverian Monarchy. At that time, it was best not to talk of such Libertarian things in polite English circles. That still has an effect in Britain, even 200 years later among the intelligentsia. The lack of awareness of this as a political dimension may help explain why the media and commentariat is so completely confused by current events. It just doesn't fit the old right-v-left political dimension (but I digress).

Next : Great Myths of the Dark Ages