Here Be Dracos!

On the sometimes-violent connections between Drake and Huguenots

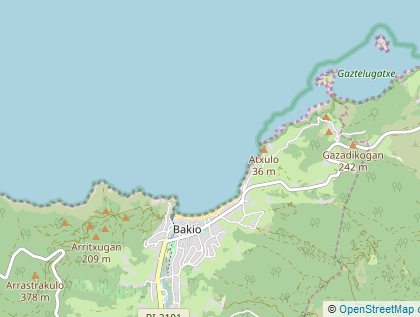

Starting on the tiny island of Gaztelugatxe, north-east of Bakio, which in turn is north-east of Bilbao, the capital of the Basque Country.

The small Basque church on the island dates from the 10th century and may have originally been used by the Knights Templar as a hermitage/beaconage. Which sounds like the Knights Templar were, there at least, keeping alive the art of beaconage for navigation. Because of the location of that beaconage, shielded to the east by the more-northerly Matxitxako headland, it is more likely it was a light for ships from the north. Like the Templar fleet of ships sailing to and from their main west coast port of La Rochelle.

Gaztelugatxe in on the north coast of Spain near the Basque city of Bilbao. La Rochelle is c.250 miles north, and the Galician port and city of A Coruña (c.350 miles west, and also beseiged by Drake), is home of the famous 2,000 year old Tower of Hercules, modeled after the Lighthouse of Alexandria. That too is shielded to the east by more-northerly headlands, so would have been at its most effective for ships to the north, heading to and fro across the Bay of Biscay in the direction of Ireland and South West England.

Sir Francis Drake and the Huguenots of La Rochelle both took a dim view of any Spanish control of Gaztelugatxe and neighbouring sea ports. Drake attacked and sacked Gaztelugatxe in 1593 and the Huguenots did the same in 1594. This might not be a coincidence; when Drake returned to Europe, nearing the end of his famous circumnavigation, he briefly stopped in La Rochelle to unload part of his treasure of gold and silver. This part of the cargo was never included in the official quantities landed shortly after in Plymouth.

Ref : The Secret Voyage of Sir Francis Drake

Why was that?

The mostly likely explanations are either that Drake was stashing a part of the booty out of reach of the English Crown, or that Drake was repaying his Huguenot financiers. Both things are possible without contradiction. La Rochelle had been the home of the Western Templar Fleet and their war against the Vatican Church. While the Templars were (officially) long gone, the Huguenot community was strong in that part of France. Drake had been actively working with, and fighting alongside, Huguenot naval forces for 20 years, and was well connected with them.

Well-known protestant corsairs: In 1523, Jean Forin (or Fleury), captain of the corsair fleet belonging to the ship-owner in Dieppe Jean Ango, captured a Spanish galleon containing Moctezuma's treasure, which Cortez was sending to Charle Quint. ... Between 1536 and 1568, 152 ships were captured in the Caribbean and 37 between Spain, the Canary Islands and the Azores (although not all of them by Huguenots)... In 1573 (or 1572) another Huguenot, Guillaume Le Testut, a corsair who was a member of the Dieppe school of cartography, joined forces with Francis Drake. (They) attacked a large convoy bringing gold and silver from Peru, after having put out of action a strong Spanish escort.

Ref : Huguenot pirates in the 16th century.

It's worth a slight detour for a brief review of what we know about the Huguenots, and how many of them arrived in Britain.

Huguenots, a term of uncertain origin, were French-speaking (and some Walloon-speaking) protestants of Calvinistic temper, who fled from two centuries of persecution to seek asylum and freedom of worship in countries more sympathetic to Reformation practices. After the St Bartholomew's Day massacre (1572), the first wave of refugees to Britain were received at already established French churches in London, Canterbury, and Norwich, but hopes that their exile would be short soon faded. Relative quiet in France lasted only until 1661, when there commenced a steady erosion of privileges, culminating in the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes (1685), after which the trickle of emigrés became a flood, then a torrent. Some 40,000–50,000 Huguenots are estimated to have settled in England, the majority in London (those associated with the silk trade around Spitalfields, professional families in Leicester Fields/Soho) but other communities in East Anglia, the south/south-west, and at Edinburgh; 10,000 are estimated to have settled in Ireland. ... A distinct minority element, but deriving much support from their close-knit communities and their faith, they proved highly-motivated, productive, and a considerable economic asset to their new host nation.

Ref : John Cannon, The Oxford Companion to British History, 2002

Deeper insights can be found here : Fortress of the Soul: Violence, Metaphysics, and Material Life in the Huguenots' New World, 1517-1751 (Early America: History, Context, Culture) by Neil Kamil

or ; Extracts

Eventually they (together with the Manichean Albigenses) grew so numerous that they became a threat to the very existence of the Roman Catholic Church.

Manichaeism being an alternative early form of Christianity that (for a while) competed with Roman Christianity. It included influences from the teachings of Gautama Buddha, Zoroaster, and Jesus.

The Huguenots were French Protestants who, if one counts their forerunners the Waldensians, were persecuted with varying intensity for five or 6 centuries right up to the coming of Napoleon. Their forerunners, the Waldensians, arose in the 12th century and were led by Peter Waldo, a rich merchant of Lyons who, at a time when the Holy Scriptures were a closed book, declared the Bible to be the only rule of faith and life, and used lay preachers to proclaim the Gospel. The Waldensians did not believe in the doctrine of purgatory, and they rejected prayers and masses for the dead. Eventually they (together with the Manichean Albigenses) grew so numerous that they became a threat to the very existence of the Roman Catholic Church. They were declared heretics and fearfully persecuted by the Inquisition and the armies of Pope Innocent III. It is said that for twenty years "blood flowed like water." As a result, the fairest provinces of Southern France were turned into a wilderness, and their cities into ruins. The Albigenses were rooted out, and the Waldensians who survived were later integrated with the Huguenots.

Ref : John Cannon, The Oxford Companion to British History, 2002

Not believing in the Doctrine of Purgatory was dangerous? Yes, when the main Roman Christian franchise was keen to sell that doctrine and to remove all competitors from the market for peoples' souls.

The origin of Huguenot beliefs (and perhaps of some of the Huguenots themselves) lies among the Cathars in the medieval past of the eastern Mediterranean.

http://www.artandpopularculture.com/Huguenot

Like being a Cathar was dangerous?

The Cathars awaited a Messiah who would be the son of a widow; like Parzival. One of their symbols was the dove, which according to Wolfram was the bird that brought a wafer to the Grail on each Good Friday. It is also said that they believed in reincarnation, and that through good works one could obtain redemption from sins committed in a previous life.

Ref : Catharism and the Albigensian Crusade

These Grael connections are very significant; both for the mythology, and what has been derived from it.

The Parzival story is geographically based in the Basque part of Spain and South West France.

It is thought that Wolfram began writing Parzival in about 1200. At this time there were several different religious sects in what is now southern France, the Oc region or Languedoc, and in particular around the town of Albi. The Albigensians or Cathars were a sect with dualistic beliefs similar to those of the Manicheans.

Ref : Catharism and the Albigensian Crusade

The remaining descendants of the Cathars and Albigensians (via the Waldensians and Huguenots) bought their version of the Grael legends back to Britain as a deeply-embedded folk memory intertwined with the persecution by the Catholic Inquisition.

In one sense it is sad to think of how great a treasure was lost to France by the emigration of such a people — though that sadness cannot but be tinged with an ironic delight at how England benefited from all that these newcomers were able to offer in their new homeland: tapestry making in Exeter, silk and cotton manufacture in Bideford, sail-making in Ipswich, papermaking in Southampton, hat-styling in Wandsworth and language teaching in Cheam. And that is but a random selection from the range of skills that these scholars and craftsmen, whethers employers or employed, were able to share with the English. And it is in one Craft in particular that we should be particularly interested this evening to hear of their involvement. For make no mistake, the place of the Huguenot male citizen of the early 18th century in the development and establishing of the English Grand Lodge was notable and extensive.

Ref : Did You Know This Too?, by Revd. Neville Barker Cryer, pp.87/91

The inflow of Huguenot trade skills into England through south and east coast ports bought with it a rich influx of Huguenot learning, ideas, beliefs and attitudes.

This is well-described in The Visual Theology of the Huguenots by Randal Carter Working, which shows how, in the 16th century, Protestant architects and designers deliberately adopted a Vitruvius style of Renaissance architecture, different from the Gothic style used by the Catholic church.

(Vitruvius') discussion of perfect proportion in architecture and the human body led to the famous Renaissance drawing by Leonardo da Vinci of Vitruvian Man ("The proportions of the human body according to Vitruvius").

A Huguenot example of this is Bernard Palissy, who demonstrated that "Protestants saw all of nature as reflective of God's presence and benign purpose". Unlike the Catholic symbology of "sacralised material objects" and of a God to be feared.

On the other hand: We have the "function of sacred violence and alchemy in the visual language of Huguenot artisans". Did this appeal to Drake? He had plenty of exposure to Huguenots, was financed by them, and was no stranger to violence and taking the battle to the enemy.

English school history tends to only mention his role in the war with Spain. His role in the wars closer to home (against Catholics in Ireland and Scotland) does not get much of a mention. Which gives me a uncomfortable feeling; perhaps because he was involved in the killing of some of my Scottish ancestors. Or perhaps it's all a bit too politically-incorrect to mention it these days?

Next : The Grael goes Dutch